Compared with other industries, software development stands out for how quickly AI and large language models have become commonplace. Data from Anthropic shows that computer and mathematical jobs, which include roles like software engineering and data science, represent less than 5% of the US workforce, but nearly 40% of the conversations with Claude.

But LLMs have a scaling problem. Production codebases are often too large for a model to fully read and reason about in a single chat or coding session. Even when more material fits into the prompt, longer context often makes models less effective. Benchmarks from Adobe Research’s NoLiMa show that newer models such as GPT-4.1 can lose 20% or more in performance when context length increases to 32K tokens (roughly 24K words). For slightly older models, such as Gemini 2.5 Flash, the drop in performance can exceed 50%.

To solve this problem, developers are getting creative. One solution is to summarize large codebases into shorter documents and feed them to LLMs, rather than sending massive chunks of raw code with every chat. Developers can describe the design, structure, and style of their projects in concise files to guide LLMs while keeping context length in check.

This has led to the proliferation of new types of repository artifacts — files written in natural language that live alongside code and designed for quick consumption by agents. The most popular file type is known as AGENTS.md. Its creators describe it as "a dedicated, predictable place to provide the context and instructions to help AI coding agents work on your project." These files contain test commands, code style guidelines, security considerations, and more.

But how popular is this new standard and how are these documents typically structured? Based on an analysis of the 100 companies with the most open-source contributions on GitHub over the past year—including large, household-name companies like Shopify, Google, and Meta—usage of AGENTS.md looks promising but is far from universal. Just 32 of those 100 companies had at least one public repository that included an AGENTS.md file. While that is meaningful early adoption, it also suggests the standard is still in a formative phase.

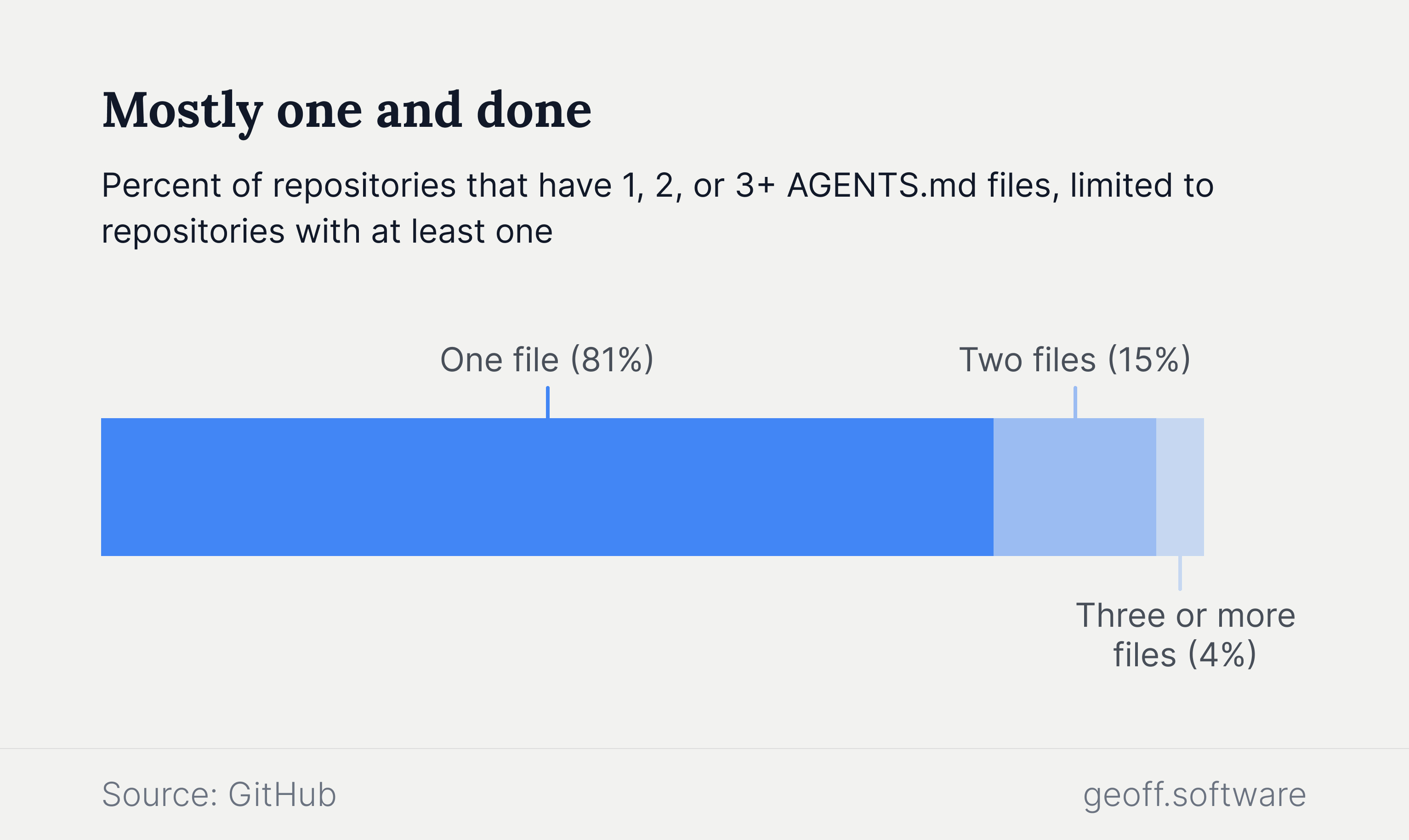

Implementation of AGENTS.md files is inconsistent as well. Most repositories include a single AGENTS.md, but some use several. About 20% of repos that have an AGENTS.md include more than one. This is especially common in modular monoliths, where different services benefit from having their own localized context.

A typical AGENTS.md file is short, with a median length of 930 words across 180 lines. Code blocks make up about 18% of those lines. Links are uncommon. A majority, about 55% of files, contain no links at all. Despite their brevity, AGENTS.md files have a median reading grade level of 14, based on Flesch Kincaid tests, suggesting they are written for a highly technical audience.

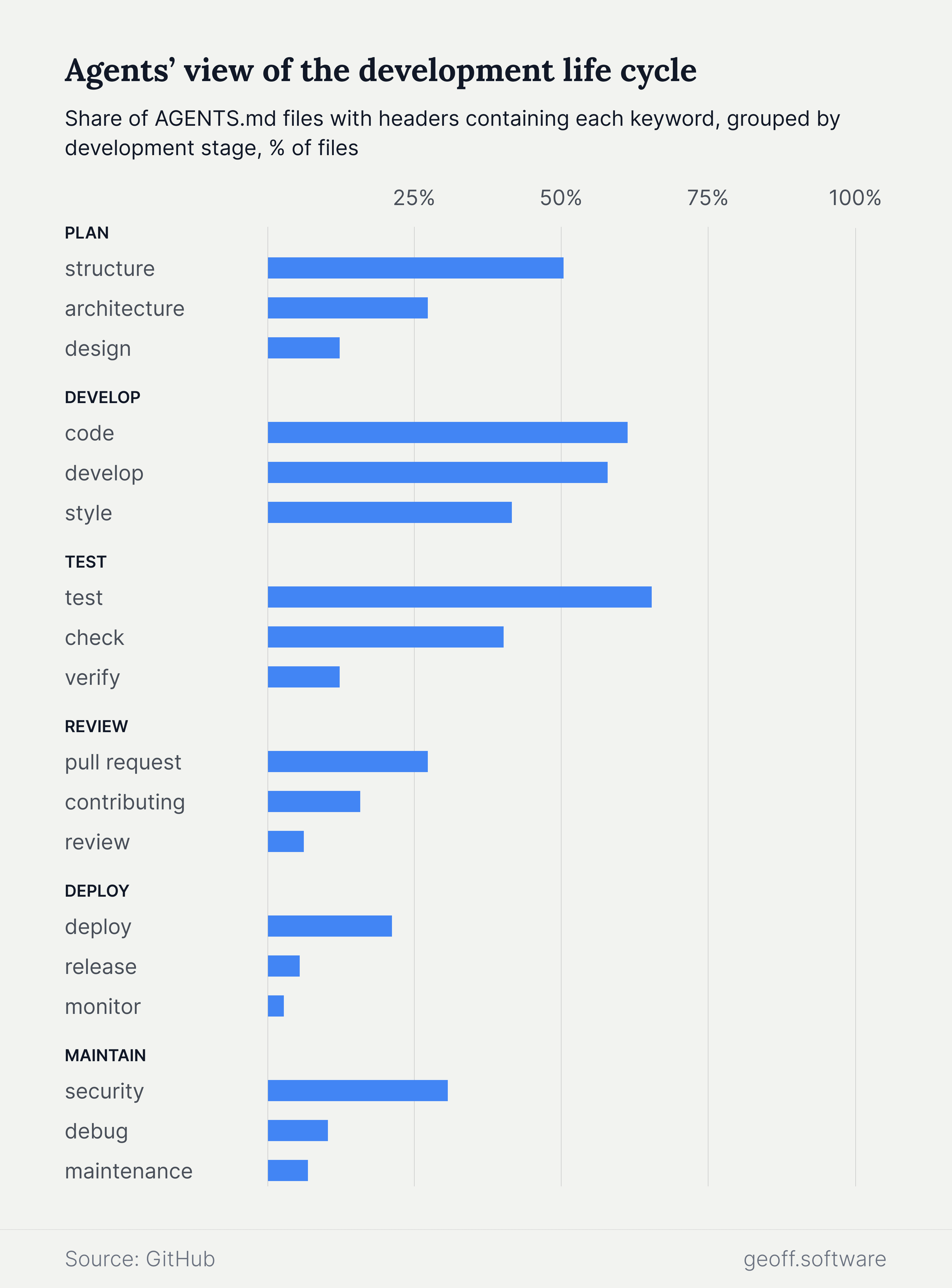

Headers and subheaders in AGENTS.md files offer a useful signal about what developers consider most important for agents. Most files contain headers focusing on concrete guidance around coding and testing, a clue into how much of day-to-day development work developers might be trying to offload to agents. Other headers, like those focused on design and architecture, point to a broader shift toward using agents earlier in development workflows, especially for planning and scoping work. Tools like Devin, which its creators position as an autonomous AI engineer, are explicitly aimed at that kind of end-to-end contribution.

Do AGENTS.md files need more standardized structure? The question is complicated by the fact that these documents are often written by the AI tools themselves. Verbose models can draft content quickly and frequently, sometimes faster than developers can review it. Without shared conventions for what belongs in these files, the result can be a new kind of content debt where agent-facing documents grow without clear boundaries.

One promising solution is self-updating documentation. In this workflow, agents do not just consume context, they also maintain it as they work, refreshing instructions and pruning what no longer applies. Documentation becomes part of the development loop, written not only for human teammates, but for an agent’s future self.

The scaffolding for stronger standards exists, but much remains to be filled in. Most teams base their AGENTS.md files on examples and broad guidelines rather than clear norms. Best practices emerge through trial and error and are passed between teams through word of mouth.

Even without a clear consensus on how they should work, AGENTS.md files are becoming an integral part of development work. They are just the leading edge of a much larger shift: the codebase is becoming more than a home for production code. It is turning into a working environment where context and code live side by side.